Guaranteed Basic Income

In Ann Arbor, city officials decided to use $1.6 million of the city’s $24 million in fiscal recovery funding to create what will be the state’s first guaranteed basic income program.

For two years, the city will provide 100 low-income families with a monthly $500 check — no strings attached.

City Council member Linh Song proposed the pilot program last spring as she saw Congress let an enhanced child tax credit and COVID eviction moratorium expire.

“Even though Ann Arbor is an economic engine of (Washtenaw) County and fairly wealthy… there are folks who can barely afford to stay here or have been pushed out,” Song told Bridge Michigan, explaining her motivation.

“I really wanted to see (the pandemic recovery money) hit families locally to address these really immediate needs.”

Guaranteed Basic Income, and its broader cousin Universal Basic Income, aren’t new concepts. Alaska has used oil revenues to pay residents an annual dividend since 1982. And presidential candidate Andrew Yang turned heads by proposing a national “Freedom Dividend” in his 2020 campaign

Stockton, California, began a municipal basic income program for low-income residents in 2019 and dozens of other cities have followed. Lansing Mayor Andy Schor proposed using federal recovery funds for a similar initiative, and Detroit explored the idea too.

While critics argue the programs could discourage work and are too expensive, early research points to mental health and financial stability benefits for recipients.

More than a year after approving funding for a guaranteed basic income program, Ann Arbor is still in the planning stages.

But on June 5, the City Council is poised to vote on a contract for the University of Michigan’s Poverty Solutions to both administer and evaluate the pilot effort.

“It was really important to the city… that we find a partner who could produce usable social science that can be passed on to other cities or other states or nonprofits who are interested in running their own,” deputy city administrator John Fornier told Bridge.

While initially limited to 100 low-income families, the pilot program could “set the foundation for a larger, longer program that could benefit all families in Ann Arbor,” the city said in a report to the federal government.

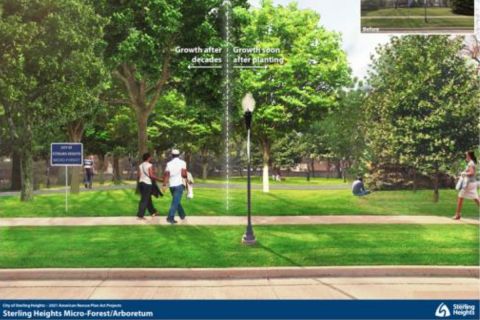

‘Micro-forests’

The state and large local governments have so far announced plans to use $1.4 billion in federal stimulus funds to replace revenue lost during the COVID-19 pandemic and provide general government services, including $1.1 billion already spent.

The broad spending category, as defined by the federal government, allows spending on a wide array of projects.

Sterling Heights is spending $1 million of its $19.8 million in federal stimulus funds to create a series of “micro-forests” by planting trees throughout the city.

Locations could include downtown, public parks, corporate campuses, industrial areas and “really, anywhere there is 1,000 square feet of vacant land,” officials said in a federal report.

The project, the city added, “is justified by the tremendous environmental benefits derived from a forest, including cleaner air, a natural water filtration system, a natural air conditioner, a flood mitigation system, a natural habitat for all forms of life, a natural recreational amenity for people seeking peace and quiet.”

Sterling Heights is a dense community that is “pretty much fully built out,” Mayor Michael Taylor told Bridge. “Every nook and cranny of the community continues to get developed. But as developers come in, they’re clearing trees.”

Replacing trees by planting micro-forests will help the city meet sustainability goals and increase quality of life for residents, Taylor said. “And it’s great for the environment.”

Government jobs, premium pay and lost revenue

The state and local governments are so far planning to use a relatively small portion of their federal recovery funds to plug holes in their own budgets or staffs, including $321 million already spent to make up for lost revenue, $256 million earmarked to hire or retain employees and $24 million to provide premium pay to workers who stayed on the job during the pandemic.

Genesee County was the largest spender on this front, using $7 million to provide bonus pay to more than 1,000 government employees — an average of about $6,500 per county worker.

County government offices closed “for a brief period of time” during the COVID-19 pandemic but quickly re-opened to serve the public, Genesse officials said in a federal spending report.

Employees who returned for in-person work were “an integral part” of keeping the county operational, developing COVID response plans, delivering meals to home-bound residents and helping schedule and administer vaccines, the county added.

“The on-site work of these positions were key to keep the county functioning during this timeframe and there were additional risks for these staff by being in-person in contact with others.”

Digging up lead pipes

Heading into 2023, the state of Michigan and its largest local governments had finalized plans to use a combined $1.4 billion in federal recovery funding for infrastructure improvements, according to federal reports.

But only $25 million had been spent.

Much of the money has been set aside for water infrastructure projects, including about $1 billion the state budgeted for new drinking and clean water revolving funds that will be able to loan money to local governments for related projects.

The state also used $92 million to help Detroit and Benton Harbor tear out and replace underground lead service lines.

Other communities including Bay City ($6 million) are using their own federal funds to replace those pipes, as required by 2040 under a rule former Gov. Rick Snyder implemented in the wake of the Flint contamination crisis.

It’s a huge undertaking: As of 2021, officials estimated there were still more than 400,000 active lead water lines in communities across the state, posing a potential risk to public health.

“You do tend to see people doing projects that maybe they were planning to do anyway, so they’re just using this money to pay for a few miles of road or to fix some lead service lines,” Scorsone said. “And that’s good. They free up money for other things.”

Public health and gun violence

The state and local governments had set aside $788 million in federal recovery dollars for public health initiatives through the end of 2022, and spent about $200 million of that.

Much of that money is intended for direct responses to the pandemic, including a combined $139 million for equipment at nursing homes and other congregate settings. At least two communities — Saginaw and Lenawee County — used funding to incentivize government employees to get COVID-19 vaccines.

But local governments also plan to use the stimulus funds to address other public health issues exacerbated by the pandemic, including $20 million for mental health efforts in Oakland County and nearly $8 million for a gun violence reduction plan in Detroit.