Greco, the renowned Cretan iconographer Andreas Pavias and a famous Constantinople embroiderer “weave” with colors and threads the passions of Jesus in precious works of art.

- Easter in Athens: 4 works of art at EPMAS, B.&E Foundation. Goulandris, Benaki Museum and Kanellopoulou Museum

- The Crucifixion – Andreas Pavias (d. 1440-between 1504-1512)

- The divine form (LaSantaFaz) – Domenikos Theotokopoulos /ElGreek (1541-1614)

- Epitaph with representation of The Lament – Despoinetta (1682-1723)

- Image showing Pieta-Removal

Easter in Athens: 4 works of art at EPMAS, B.&E Foundation. Goulandris, Benaki Museum and Kanellopoulou Museum

The Crucifixion – Andreas Pavias (d. 1440-between 1504-1512)

National Gallery

Andreas Pavias, The Crucifixion

On the first floor of EPMAS, opposite Greco’s creations, the Crucifixion of Christ and the Two Robbers by Andreas Pavia (from the Bequest of Alexandros Soutzos) stands out among the works of post-Byzantine painting. Rendered with egg tempera on a wooden board, i.e. with the traditional Byzantine technique, it is a work of the second half of the 15u century. The multi-faceted scene, loaded with episodes and full of drama, unfolds on a golden plain.

As Professor Marina Lambraki-Plaka pointed out: “The golden depth in Byzantine art suggests the sky and reminds us that we are dealing with an idealistic and not a realistic painting; that is, with divine, transcendent figures, who live outside of place and time, in infinite spacetime. The figures seem self-illuminated, not illuminated by an external light source.”

Observing the image, we can see that it develops in three levels. On the lower left is depicted the resurrection of the dead, who we see coming out of their graves, while on the right (above his signature) the important Cretan iconographer from Khandaka represented the soldiers playing dice with the purple robe of Christ.

On the second level we see the motley, colorful crowd present at the tragic event, with the fainting Virgin in the center, supported by women and John, while Magdalene mournfully embraces the cross. Around them, a motley, colorful crowd in exotic clothing, hats and horses surround the scene.

In the upper part, where the crosses with the bodies of Christ and the two robbers are projected, mourning angels fly, while others collect in chalices the blood of Jesus. A polygonal building in the background on the left is reminiscent of the temple of the Holy Sepulcher. There is no shortage of details, each with its own meaning – for example the stork above the Holy Cross that pierces its breast to feed its children and symbolizes the sacrifice of Christ, in order to save man from original sin.

The divine form (La Santa Faz) – Domenikos Theotokopoulos / El Greek (1541-1614)

B. & E. Goulandris Foundation

El Greco, The Divine Form © Jacques Viemon

The legend of Saint Veronica, which since the 15th century occupied many great painters, such as Dürer, Bosch, Podormos and Correzzo, gave “food” to the painter of Theotokopoulos (from 1577 onwards) to approach the established in the Catholic iconography theme of the Divine Form.

Ascending the road to Calvary, carrying the cross of martyrdom, Jesus Christ falls. A young woman bends over him and offers him the veil she wears. Jesus takes it, wipes the blood and sweat from his face, and hands it back to her. Amazed, she sees the imprint of his face on the cloth, the Divine Form that gives the unique oil painting with a religious theme in the collection of the B. & E. Goulandris Foundation its title. It is one of the seven paintings by the great Cretan that we find in Athenian museums (the others in the National Gallery and in Benaki).

Either alone or in collaboration with his studio students, Greco creates several works with this theme. In others it focuses solely on Christ, while in others it also represents the veil. Of particular interest in this oil painting (51 x 66 cm) is how he manages to combine the aesthetic references from Eastern and Western cultures, Orthodoxy and Catholicism, which he assimilated along the way.

“He spends a lot of time working out the folds, the anchor points, the variations in lighting in detail. Thus, the face of Christ appears even more harmonious, almost undulating on the moving and light-bathed surface, which in turn seems to emerge from the dark background”, says the Maria Koutsomalli-Mororesponsible for the Foundation’s collection.

If the visual treatment remains faithful to what he learned first in Venice and then in Rome, the impassive face of Christ shows the influence from the orthodox tradition. “The physical pain and agony of the sacrifice do not appear; the gaze seems already directed towards eternity; no source of external light is visible, one might say that Christ himself is shining. The sunken cheeks, the long face, the almond-shaped eyes, characteristic of Greco’s painting, give him a gentleness and grace. Not even the wounds from the crown of thorns affect him: the whole journey to Calvary is symbolized without unnecessary melodramatism by a drop of blood flowing down the center of the forehead.

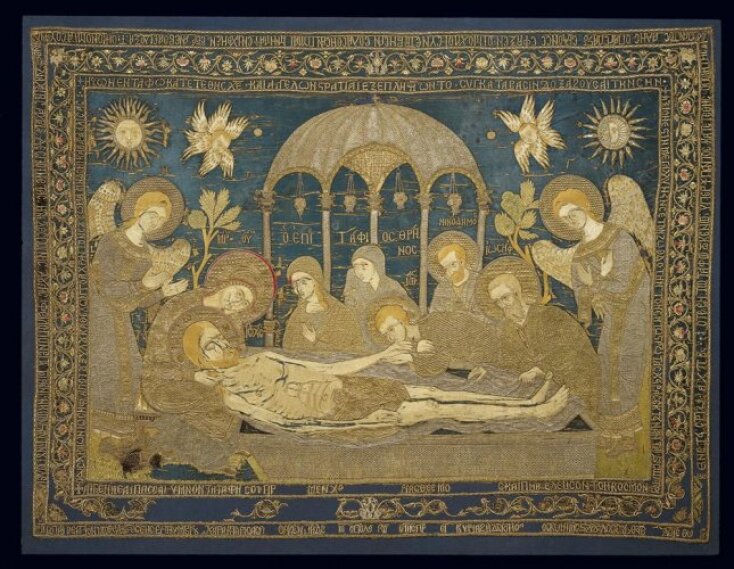

Epitaph with representation of The Lament – Despoinetta (1682-1723)

Benaki Museum

Despoinetta, Epitaph with representation of The Lament © Benaki Museum

With gold and silver thread on silk, the elaborate lament scene embroidery, rendered by the famous archdeastre Despoinetta in 1682, commands our attention in room 26 on the first floor of the Museum of Hellenic Culture in the heart of Athens. It sits among other works of ecclesiastical art and a few rooms beyond the magnificent works of craftsmanship created by women and men from all over the Greek world between the 16th and 19th centuries.

A balanced composition, it presents the body of Christ over which the mourning figures are bent, in front of a dome with columns, from the arches of which four lamps hang. Blue silk colors the sky where the sun, moon and two cherubs hover above trees emerging from the cluster of figures. Confronting the figure of the Virgin Mary supporting Christ’s head and John kissing his hand, you can’t help but perceive the emotional intensity of the moment. The performance is flanked by two films with inscriptions – which provide information about the scene by quoting passages from Good Friday tropes – and are separated by lotus panels. In the signature we read: “by the hand of a lewd Miss” (“lewd” because of her sins).

As Dr. Giorgis Magginis, scientific director of the Benaki Museum, informs us: “The orders of similar fabrics were the most expensive for the ecclesiastical authorities of the Ottoman period and their embroiderers, mainly women, were famous. One of them was Despinetta. Her workshop was in Istanbul, but she received orders from Cyprus, Alexandria, Sinai, and even Romania. She employed many apprentices and was one of the many embroiderers who worked in their private workshops in the capital of the Ottoman Empire. On this epitaph, commissioned by the Greek Orthodox Metropolitan Cathedral of Ankara, her signature occupies a prominent position, behind the head of Christ, emphasizing the prestige of the artist, a member of a minority in a Muslim empire during the seventeenth century.”

Image showing Pieta-Removal

Mproperty of Pavlos and Alexandra Kanellopoulou

Image with Pieta-Removal performance © Pavlos and Alexandras Kanellopoulou Museum

The Deposition, the charged moment when Christ’s body is taken down from the cross to be buried, has inspired many works of painting and sculpture.

The image of the Kanellopoulos Museum in Plaka, work of the 16th centuryu century, bears a representation of Pieta-Apokahilosis. Christ, with his body naked and his girdle tied low, projects through an altar and in front of a cross. He is held by the Virgin on the left and Saint John on the right, while Joseph is seen behind, holding the dead body with his palm.

According to the professor of Byzantine archeology at the University of Ioannina Nano Hatzidakis: “The image is characterized by the expressiveness of the forms and masterfully combines iconographic and stylistic elements of Western painting and the Byzantine tradition, as shaped by Cretan artists and not only workshops of the 15th and 16th centuries. Although unsigned, it carries models from well-known works of Venetian painting of the period. It also shows similarities with an image of a similar theme that has been attributed to the painter Ioannis Permeniatis, who has been associated with the Knighthood of Rhodes and is reported to be active in Venice in 1523”.