Few dared to believe it, although an agreement seemed close this time, closer than ever since the asylum crisis of 2015. Unanimity was not however required to validate these reforms, which finally establish the balance between the responsibility that weighs on the Member States drawing the Union’s border to manage migration and, on the other hand, the European solidarity on which they must be able to count in order to meet this challenge. But the split between the 27 was such that the compromise put on the table by Sweden, which holds the Presidency of the Council of the EU, even had difficulty in bringing together a qualified majority of Member States (minimum 15, representing 65% of the European population).

Above all, that you don’t need just any majority. Poland and Hungary, strong critics of migration, had shown their opposition from the outset, so their negative vote was taken for granted. Hungarian Minister Bence Retvari has also warned: “I will raise this subject at the European Council”, at the level of the leaders of the Twenty-seven. This is where Hungary would have liked to see the debate end, since there decisions are made by consensus. Thursday, the challenge was above all to rally the first concerned by the migratory pressure, such as Greece, Cyprus, Malta and especially Italy. But on Thursday at the end of the afternoon, after hours of debate – “sterile”in the words of a diplomat – and negotiations, these countries expressed, in turn, their reservations… Sweden, however, continued efforts to find in extremis a solution, convinced that it’s now or never to conclude an agreement. “There is no excuse not to reach an agreement”warned Maria Malmer Stenergard, Swedish Immigration Minister.

The head of the Greek government poses as a “bulwark” of Greece and Europe against the “invasion of migrants”

If Malta abstained, Italy finally ended up joining the compromise, which wants to be the best possible to satisfy the extremely opposed positions of the Twenty-seven. After all, he “displeases everyone equally”, as observed at the start of the meeting, Nicole de Moor, Belgian State Secretary for Asylum and Migration. At the time of writing these lines, not all of the last-minute changes that made it possible to extract an agreement on the major points of tension were known.

Mandatory procedures at the border

This is one of the great novelties: establishing procedures at the borders of the Union, in order to assess from the outset the chances of an asylum seeker of obtaining refugee status. This task will therefore fall to the Member States located at the front line of arrivals and which would therefore be obliged – in addition to registering the migrants who arrive, as they currently do (in theory) – to carry out this preliminary “sorting”, just entry into their territory.

This “express” asylum procedure is supposed to last a maximum of 12 weeks (or 16 in exceptional cases). Either the migrant can claim asylum, given the situation in his country of origin and his individual case (risk of persecution for his political opinions, his sexual identity, etc.). In this case, the person must be authorized to enter the territory of the Member State, to be accommodated there for the time required to follow a “classic” asylum application procedure.

Either it is considered that the asylum seeker has little chance of obtaining international protection. This is particularly the case if the positive decisions issued for his compatriots represent less than 20% of the decisions concerning the nationals of this third country. The personal situation of this individual will still be assessed, but in an accelerated manner. If there is no indication that he needs protection, he will have to return to his country of origin or… even to another, as long as he does not incur any danger there.

Express returns, yes, but to which safe third countries?

Here comes the concept of “safe country” and thus one of the points of tension between the Member States. The acceleration of returns – to the point of carrying them out in a few weeks, within the framework of the border procedure – almost conditions the success of this new system. In order to achieve this, the will shared by all the Twenty-seven is therefore to multiply the agreements with many countries, to send back rejected asylum applicants. Even if it means making the EU more dependent on other states for its migration policy…

However, the question arises of a more or less strong “link” which must still exist between the migrant and the “safe third country” (in addition to his country of origin) to which he could be returned. Various criteria were mentioned (a previous stay, family, linguistic or cultural ties, etc.). Some Member States, starting with those under strong migratory pressure, nevertheless considered that a simple passage through this country on the way to the Union would be sufficient, or even that at this stage we should not be encumbered with criteria at all . Requiring the least possible constraints, Italy, supported by Malta or Austria, had made Thursday afternoon a reason to reject the agreement… Rome will have finally ruled out “restrictions which would have excluded certain third countries”.

Detention camps?

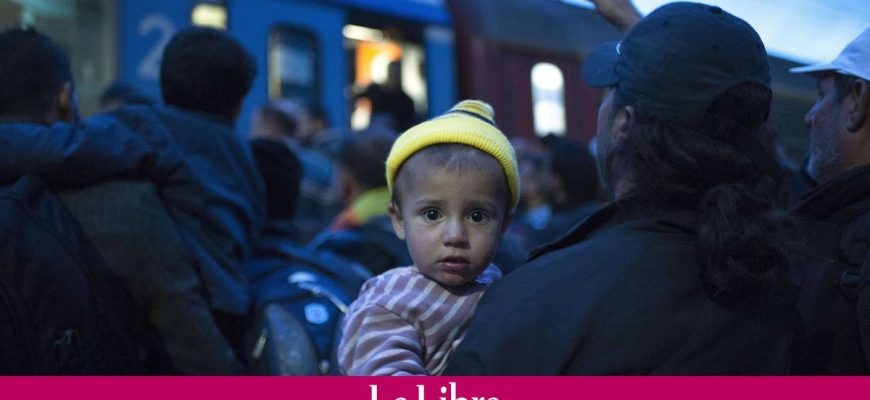

The compromise provides that migrants can be detained for the duration of this border procedure. However, the experience of the “hotspots” has shown the Union how much this idea of quickly “sorting” migrants at its borders can be illusory. In 2016, it was this “solution” that was implemented on the Greek islands, which have become open-air detention centers, as part of the agreement with Turkey to reduce migratory flows to the EU. History will remember above all the images of thousands of migrants crammed into overcrowded camps, condemned to live in unsanitary conditions, while the Greek system was saturated, while decisions on asylum applications dragged on, as did the returns of Syrians to Turkey, provided for in the agreement.

‘I am denied the right to be with my foreign wife in my own country’: Danes victim of tougher immigration laws

“The border proposal is just a carbon copy of the failed model seen on the Greek islands. It will lock refugees, including children, at enormous cost, in prison-like centers on the far reaches of the Europe”, lamented the NGO Oxfam. But if the principle of detention was accepted, it was the fate of children that divided the Member States. Germany, like Belgium, were among those who pleaded not to lock up unaccompanied minors or families with children under the age of twelve. But others weren’t too keen on making exceptions. “We must prevent children from being sent on a very dangerous journey to Europe“, pleaded the Dutch minister.

Ultimately, the children will not be able to be locked up, confirmed Secretary of State de Moor.

A (more or less) reformed Dublin regulation

Despite the promises of European funds, the countries of the South know to what extent this procedure risks being an operational and administrative challenge. But above all, a heavy political responsibility. Because under the Dublin Regulation, it is the Member States through which a migrant entered the Union that is responsible for processing his asylum application, accepting him or returning him.

This principle will not disappear. On the contrary, “Dublin would be operational again”, summed up a European diplomat on Wednesday. The period during which a State of first entry is responsible for a migrant was even to be extended from one year to two years. This is intended to be a guarantee for countries, such as Belgium, which are the destination of “secondary movements” of migrants who nevertheless continue their journey in the Union and the European free movement area. These can (in theory) be sent back – “dublinized” in European jargon – to the States of first entry as long as they are responsible for it. But this system has struggled – to put it mildly – in recent years. Complaining about the lack of solidarity from others, countries of first entry suspend or make these transfers difficult, when they do not manage not to register migrants entering their territory at all and thus free themselves from them…

Solidarity becomes mandatory, but not relocation…

That is the whole point: trying to put an end to this situation, synonymous with migratory chaos in the minds of many voters. “From a political point of view, you can win or lose elections on migration in any Member State”, noted a European source on Wednesday. And one thing is clear: the entire burden of managing migration cannot rest on the countries of first entry. According to the proposed reform, solidarity will therefore become o-bli-ga-tory – no longer dependent on the goodwill or political constraints of each. A State could benefit from it as soon as it is subjected to excessive migratory pressure. Unsurprisingly, determining what “pressure” means has been the subject of debate.

But it is the way of expressing this solidarity which particularly divided the Twenty-seven. The countries of the South demand above all to share equitably the reception of asylum seekers across the Union. In 2015, the only attempt to fairly relocate refugees failed, leaving Europeans with political trauma. The countries of central and eastern Europe were violently opposed to it. And always oppose it.

Sweden therefore proposes to relocate at least 30,000 migrants per year in the EU, according to a distribution key which would take into account the economy and the population of the Member States. For Belgium, the percentage would be set at 3.19% of the total number of asylum seekers to be relocated. But those who do not want to lend themselves to this exercise would have other means of showing solidarity, which will be just as appreciated. They can thus provide operational assistance and above all a financial contribution. Refusing to assume its fair share of relocations would have a price: 20,000 euros per migrant that a country refuses to welcome. It was enough to provoke indignation in the east of the continent. “There can be no fine”, Pleaded the Polish Minister Grodecki. His Czech counterpart highlighted the fact that his country has taken in a large number of Ukrainian refugees – which is not discussed here, since temporary protection has been automatically granted to them. This reality applies to all Member States neighboring or close to Ukraine.

During this time, the countries of the South, such as Malta, denounced a “rather flexible and weak solidarity”. Even if Italy obtained only the “cases of migrants rescued at sea are considered to be the responsibility of the European Union”.

In the endafter repeating this debate for eight years, an agreement was finally reached.